Narrative arts and storytelling traditions in India and China

~ By Charmaine Mirza

Once Upon A Time…

According to ancient tradition a powerful and wise emperor, decided to conduct a test of empathy, selflessness and generosity. He set off into a woodland disguised as a hungry old man. He came across four friends in the forest: a monkey, an otter, a jackal and a rabbit. He begged them for something to eat as he built a fire to keep himself warm.

The monkey ran off and grabbed some fruit off the trees to bring back to the old man.

The otter dove into the river and caught a fat fish for the old man to eat.

The jackal snuck off to a neighbouring farm and stole a pot of milk curd and a lizard to provide the old man with sustenance.

But the rabbit did not know what to forage for as it only ate grass. Yet it strongly believed that it should help the old man appease his hunger. So in a moment of extreme sacrifice the rabbit threw itself upon the fire, telling the old man that he could eat him.

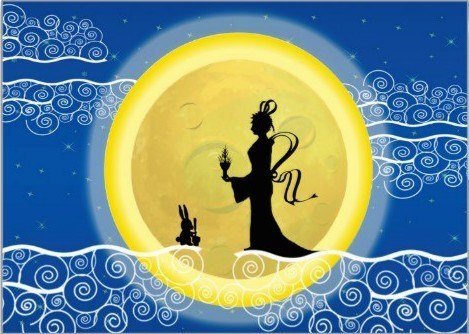

The old man reveals himself to be a wise and powerful emperor and prevents the rabbit from getting burnt. To honour his immense self-sacrifice, he immortalised the long-eared creature and sent him to the moon. That’s why when we look up at a full moon especially the Harvest Moon, we can see the rabbit pounding away with a pestle to create the Elixir of Immortality, under the benevolent eye of the Moon Goddess, who is the keeper of our emotions.

In Indian tradition, the wise and powerful emperor is none other than Lord Buddha.

In Chinese tradition, the wise and powerful emperor is the Jade Emperor.

But whether you want to call it collective consciousness, or whether you believe that there is a common thread to this narrative, the story is the same.So where does it originate?

The Roots of A Collective Consciousness:

Centuries ago, wise men from across Asia made their way across the Himalayas (a journey that could well be described to the moon and back) chasing after the elusive rabbit in search of the Elixir of Life.

What they discovered was a fount of wisdom that perpetrated itself in oral tradition. Many of these fables and folk tales were rooted in ancient Hinduism (Panchatantra) and Buddhism (Jataka). It was the latter that found the widest appeal and made its way across the Himalayan massif into corners of the world as far-flung as Persia, Indonesia, Japan, and of course, China. They later even spread as far as Europe.

Storytelling is etched into the DNA of human history. In fact, after the Bible, it’s the Jataka that is the second most widely spread narrative in the world — and the fabric of both is very similar.

Fables often draw their lessons from the natural world, using animals to illustrate human traits and characteristics. They are a timeless method of instilling values and morals in every generation of human history. Storytelling is an intrinsic part of both Chinese and Indian culture.

Minstrel Muse…

India has always had a long tradition of Katha (story). From the Joshis of Rajasthan to the Bauls of Bengal, to the Haridasu’s of Andhra Pradesh – these minstrels wander blending spirituality with song to sing for their supper. There’s a tongue-in-cheek pragmatism and worldliness in these singalong stories, and the role of the jester in amid a royal court is replicated by minstrels in everyday society.

China has an equally strong tradition of popular culture storytelling called Pingshu. Similar to Indian minstrels, they provide a form of live theatre that not only entertains, but also imparts wisdom and learning.

In an article in the Huffington Post, Yvonne Yan sheds more light on Pinghsu, “Since the mid-Qing dynasty, Pingshu gradually became an important recreational tool for people to communicate information, share interests, and enjoy their glorious history. Traditional Pingshu artists usually perform in teahouses or small theaters, where people can gather around on a nice afternoon.”

In both India and China, storytelling is a profession. It may take many years of learning and training before one becomes a full-fledged storyteller in one’s own right. Besides tales of valour, story tellers in China and India, passed on history, stories of local heroes and village romances, tales of empathy, filial piety, nationalist pride, good morals and values.

It is a re-telling from this very vein, that Inchin Closer aims to use story’s or interactive stories in their modern day avataar to help Mandarin language students practice their Mandarin. Illustrating the deep connect humans have with stories, the emotional bond that helps us to learn from tales told, Inchin Closer plans to engage learners to take a path and by choosing their way forward, decide how their individual story unfolds. For no two individuals, read a story in the same way, therefore each user of the Inchin app can play their story differently, learning new words along their path, and discovering new endings for each twist or turn taken.

Stemming from everyday situations, of going out with friends or buying products in China, the stories in the Inchin app, are practical, real world and ingrained with Chinese culture. Created to measure up to different kinds of learners, with varied interests, Mandarin language levels and experiences, the app is a modern day version of stories that hope to bind the countries by a sense of familiarity, better understanding and shared knowledge.